26 March 2019

Theorists have long claimed that our ancestors could not have formed large societies and cities without fear of vengeful gods to motivate people —but this controversial new study says otherwise.

Philosophers of religion, historians, and social theorists have long argued that early humans — and their significant transition from small tribes to cities of more than a million people about 12,000 years ago — required having faith in “moralizing gods” in order to come together and construct those expansive, functioning societies.

Without one or more deities supposedly either rewarding or punishing the people, this theory argued, nothing would get done. Humans would’ve remained as hunter-gatherers, unable to unify without this religious framework.

According to a new study, however, social cohesion and productive cooperation occurred centuries before the advent of religious order.

“It’s not the main driver of social complexity as some theories had predicted,” said University of Oxford anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse, lead author of the study published in Nature.

Whitehouse, Dr. Patrick Savage, and a team of researchers studied the records of 414 societies that sprang up across the globe in the last 10,000 years. What they found was that “megasocieties” usually formed after any evidence of faith in moralizing gods was found — rather than because of it.

Not only did the research team find that moral behavior wasn’t predicated on the fear of supernatural punishment, or karmic retribution — that social cooperation existed before these beliefs — but they even narrowed down what a population’s average size typically was before deity figures entered the picture.

“Most of the time it was right around that million-person mark, where this transition seemed to happen,” said Savage. This is when cultural and social rituals or habits such as writing morphed into rituals driven by the vindictive punishment incentives of moral gods.

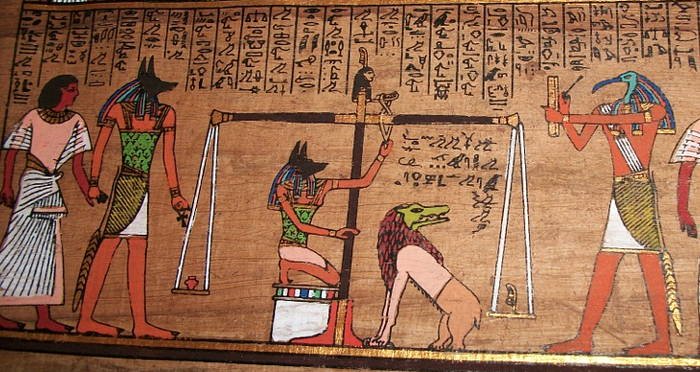

According to PBS, anthropologists, historians, and evolutionary biologists came together in 2011 to create the collection of records used in this study: the Seshat database, named after the ancient Egyptian goddess of wisdom, knowledge, and writing, and forged in hopes of gathering togther all documented information on human cultural evolution.

“Lots of this information is scattered among different books and in people’s heads, but it’s not really unified,” said Savage. “We tried to bring history together in a form where we could use big data techniques and digital humanities technologies to test big questions about human history.”

Since proving “the causal factors in the evolution of human societies” is virtually impossible by focusing on only one or two isolated moments and places in time, Seshat proved invaluable to this team. Analyzing hundreds of records from societies spread across the planet in order to distinguish patterns was far more effective than focusing on isolated evidence and thus gave the team a viable way to study their central question.

Savage and a team of about 50 other scientists used the databank to analyze 51 fundamental characteristics of human society, such as population growth, the emergence of courts and judges, irrigation, calendar use, and fiction writing.

“We could condense everything into a single dimension — that we call social complexity — and it explained 75 percent of the information contained in all 51 variables,” said Savage.

What the team found was that the moralizing gods in 20 of the 30 regions they researched — including Celtic gods in France, Hittites in Turkey, and ancestral spirits in Hawaii — did not emerge during or before the rise of social complexity, but were preceded by most fundamental social constructs.

Of course, there were significant exceptions to this, such as Peru’s Incan empire — where social habits like writing flourished only after the introduction of its vindictive god figures.

Savage and his team speculated that large groups did often seem to require an umbrella belief of potential punishment in order to maintain order. This seemed particularly so once chiefdoms, kingdoms, and leaders began to interact — and societies grew larger, and individuals more detached from one another.

“That could be a really powerful and useful way to prevent people from cheating each other, in these very large societies of unrelated people,” he said. “They need to fulfill their commitments because if they don’t, they’ll be punished by God.”

The authors essentially concluded that while a belief in supernatural punishment might’ve helped societies remain stable, and thereby continue to exist, they weren’t required for their formation.

Of course, the study has garnered quite passionate disagreement from Whitehouse and Savage’s peers, who argued that much of the data used to form this hypothesis is open to interpretation. University of British Columbia historian and religious scholar Edward Slingerland was one of the more vocal dissenters, frustrated that much of the Seshat data didn’t list any expert consultation.

“That just worries me,” he said. “I’m not saying the data is all wrong. It’s just that we don’t know — and that, in a way, is just as bad because not knowing means you can’t take seriously the analysis.”

Ultimately, the researchers did consult with dozens of experts, and Savage argued it would’ve been a fool’s errand to find enough informed scholars to analyze all 47,613 records used during the project.

In the end, he said his team is confident in the quality of its report. Considering its veracity, the theory’s fundamental claims — that human beings were capable of peaceful cooperation and productivity without the fear of violent retribution by an unseen force — are even quite uplifting.

Source: All That’s Interesting (ati)