Jan 31, 2018

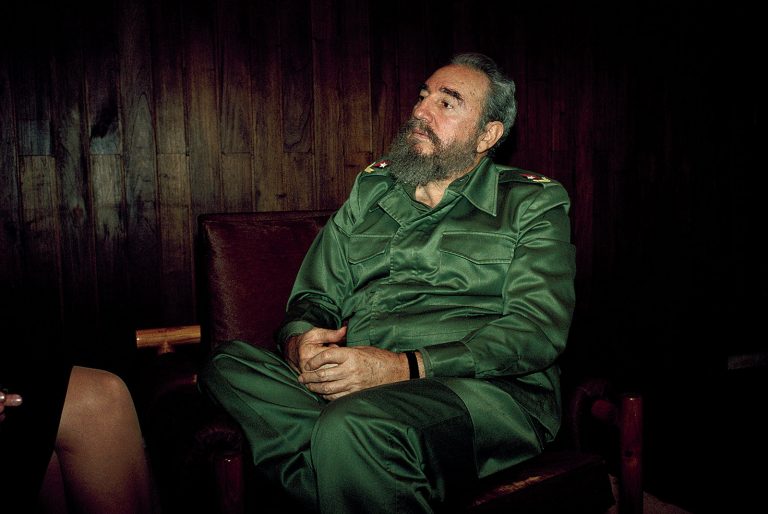

Sometime after midnight on 4 January 1994, I sat down with Fidel Castro for an interview for Vanity Fair magazine. This was my second meeting with Cuba’s ruler-for-life at the headquarters of the Communist party in the center of Havana, a city reeling from the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s patron for three decades.

The lights were out in much of the country, garbage stank in piles along the streets and people looked thin and hungry. But to describe his country’s unprecedented freefall, Castro coined a phrase, “el período especial” (“the special period”), a euphemism that suggested a party rather than an economic collapse.

After some perfunctory, softball questions, I delicately broached the topic of his retirement. After all, he was then in his mid-60s and had ruled Cuba single-handedly for 35 years, triple the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, the political role model and hero since his teen years. But he was having none of it. “My vocation is the revolution. I am a revolutionary and revolutionaries don’t retire,” he shot back, pausing for effect: “Any more than writers.”

Our interview came a year after Bill Clinton took office, and the US president was already facing accusations about womanizing. Castro, who fathered a dozen children with several different women, found such a scandal bewildering and amusing. “There are many countries where it is a good idea for the candidate, in order to be elected, to have a lot of girlfriends, where being a womanizer is a virtue,” he said. Indeed, as he spoke, his empathy for Clinton seemed to broaden. “It’s an interference in his personal life,” he protested, “a violation of his human rights.”

Asked what would happen to Cuba after his death, he said: “It’s not my fault that I haven’t died yet,” adding gleefully: “It’s not my fault that the CIA has failed to kill me.”

A worthy rival of Lazarus, Castro claimed (somewhat apocryphally) to have survived 600 assassination attempts. And he went on to make a series of Houdini-like escapes from the clutches of the grim reaper. Starting in 2001, there would be two major falls, a serious fainting episode, three major surgical disasters, and two bouts of peritonitis. By his own account, Castro believed that he almost died in 2006 during botched abdominal surgery.

A more obsessive micro-manager – of matters big and small – the world has never known. Castro had commanded every second and maneuver against the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, he famously exhorted the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, to call the bluff of the Americans and deploy missiles aimed at the US.

Likewise, he commandeered the destiny of ordinary Cubans, even those closest to him. He conceded during our interview that “we [Castro always invoked the plural “Nosotros”] may have been guilty of excessive paternalism”. Again, an interesting choice of words to describe what his critics labeled a steely, suffocating grid of Big Brother-ism.

Whether improvising one of his marathon speeches or writing a blizzard of Reflections, Castro understood that a torrent of words can both tell a story and obscure simple facts. A master of the verbal smokescreen, he set about to be his own mythographer.

In the mid-1950s, Castro had been a political prisoner (and a celebrity inmate) for about 22 months. From his cell, he never doubted the outrageous destiny that awaited him. He read and wrote ceaselessly and relentlessly plotted his political future. Those letters amply demonstrate Castro’s strategic thinking and natural leadership and are an early indicator of his Machiavellian genius for public relations.

Letter after letter illustrates Castro’s capacity to inspire others to do his bidding. He even provided the talking points: “Maintain a deceptively soft touch and smile with everyone,” he advised one cohort. “Follow the same strategy that we followed during the [Moncada] trial; defend our points of view without raising resentments. There will be enough time later to squash all the cockroaches together. Do not lose heart over anything or anyone.”

Fidel Castro sits with Celia Sánchez, left, and fellow guerrilla Haydee Santamaria in the Sierra Maestra, Cuba, in 1958. Photograph: Cubadebate/HO/EPA

Castro trusted no one, with the possible exception of his brother Raúl and Celia Sánchez, his confidante and comrade from the early 1950s.

But when Sánchez’s health began to fail in the late 1970s, Castro decided that she was better off not knowing that she was dying. For the last two years of life, Castro concocted an astonishing ruse, in which he convinced her that a noxious mold in her home was the cause of her respiratory problems, not lung cancer. Sánchez, perhaps the most beloved figure of the revolution, died in 1980 without ever knowing the nature of her illness.

Castro followed a similar template for the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who became Castro’s adoring disciple and Cuba’s patron saint who rescued the island after its economic collapse after Russia’s abrupt exit. Chávez called Castro “mi Padre” and gifted the country free oil. Suddenly a bankrupt Caribbean island was running the affairs of a country holding the largest oil reserves in the world.

So it was not an oncologist, a surgeon or family member who delivered the bad news to Chávez in 2010. Rather it was Castro, himself ailing, who informed his friend about the nature of his cancer, his treatment protocols, along with a political and public relations strategy. It was Castro who decided that the exact nature of cancer would not be revealed and Chávez would run for election again, despite being terminally ill.

When my interview with Castro ended, dawn was beginning to break over the Malecón, Havana’s majestic waterfront boulevard. I staggered back to the Hotel Nacional, called my editor and collapsed in bed. Castro, however, turned on his heels and attended to his next meeting with the three highest officials in his government. The trio had stood patiently waiting across the hall while El Jefe entertained an American reporter for hours.

It was inevitable that Castro would seek to have the last word – or about 200,000 final words – as is the case with My Life, Castro’s autobiography. According to his co-writer, Ignacio Ramonet, Castro was still glossing the text while bed-ridden in November 2006. That would mean that while the Cuban leader was dangling between life and death, being fed intravenously, 50lb (23kg) lighter and barely able to sit up, he summoned his uber-human will to rewrite his memoirs. “I wanted to finish it because I didn’t know how much time I’d have,” Castro explained.

And with his infirmity in 2006, Castro’s fierce grip on the largest island in the Caribbean finally began to loosen. Disbelief and wonder transfixed millions of Cubans on both sides of the Florida Straits. Could it be that Castro was mortal?

But as befitted one of the world’s longest-reigning heads of state, Castro would take his time leaving the stage. That exit, with periodic finales, was fated to be a marathon: his own personal epic that one might be tempted to call The Fidelia.

“Don’t worry about me,” Castro wrote his half-sister in 1954. “You know I have a heart of steel and that I will be stalwart until the last day of my life.”

And so he was.

Source : The Guardian